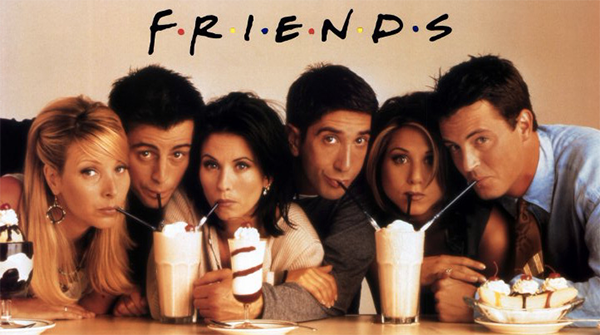

Given the release of Friends on Netflix, it seems inevitable that many, myself included, have re-watched the much-loved, and retrospectively maligned sitcom. Of course, much has already been written about the series’ attitude toward gender roles and homosexuality, and I myself have written on the questionable nature of Ross and Rachel’s apparent aspirational relationship. Now my viewing has reached the ninth season (the one in which Monica and Chandler begin trying for a baby after the birth of Emma) it is becoming increasingly apparent that the writer’s simply didn’t know what to do with Monica and Chandler after they have married.

A quick google of Monica and Chandler brings up countless articles and lists in which the pair’s relationship is consistently referred to with the positive moniker ‘couple’s goals’. Certainly, on the surface the relationship, one which originates from years of friendship before converting into romance, is admirable. Initially, the pair truly respect one another and know every facet of each other. Their relationship, being borne from so many years of friendship, is one that is rooted in equal and positive dynamics. Thus, the early days of their relationship, during the time in which they felt compelled to keep the changing nature of their friendship secret, is one that is rooted in both attraction and excitement. The pair regularly employs tactics to avoid detection but ultimately fail due to their all-consuming passion and desire for each other.

Such chemistry is long forgotten by the time season 9 arrives, and indeed long before that. The pair, when hoping to conceive a child, perform the physical side of their relationship in an entirely perfunctory manner. Following an argument, after Monica discovers that Chandler has smoked, Monica and Chandler angrily place restrictions on the act: ‘no kissing your neck’, ‘good I hate it when you do that’. The fact that the pair, who by this point have been together for several years, don’t seem to know what pleases each other is notable. The scene is played for laughs, with Chandler retaliating with the line ‘and lots of kissing your neck’, but the response, rather than sparking a conversation between the two, simply highlights that their previously passionate relationship is one that has become entirely staid with little pleasure.

The power dynamics between the two is, when watching the episodes in quick succession as I have done, rather startingly in its change. Previously, Monica and Chandler appeared to respect one another, asking for advice and discussing issues at length. Later, when Chandler is working in Tulsa, Monica readily stays In New York for a job opportunity (to which, rather positively, Chandler gives his blessing to) and quickly forgets the very presence of her husband. The group sitting in the coffee house sans Chandler, remind Monica that Chandler is not currently present when she refers to everyone being present. Monica’s realisation again played for laughs, is to exclaim her shock and surprise, but not truly register the problem. Why then, is their relationship, one that started in such a positive way, so rapidly rendered as one without true understanding or respect. Why is it one that is perceived as aspirational by so many?

The series’ presentation of marriage, or a long-term relationship, is not wholly positive. Certainly, no such relationship is free from faults, but the manner in which the audience is encouraged to both accept and laugh at the state of Monica and Chandler’s relationship is questionable. Gone is the respect, and in its place, a relationship that relies on quips and apparent witticisms to demonstrate apparent contentment.